Company Culture, Employee Well-being, Leadership & Management, Psychological Safety

“If you don't like taking a risk, you are taking a risk. You're taking the risk of stagnation, or the risk that your company or team will seize to be relevant over time … We need to continue to help people shift their mindsets from, 'I got this' to, 'I wonder what would happen if …'“

Amy Edmondson, Novartis professor of leadership and management at Harvard Business School, and renowned for her research on psychological safety, joins the Better podcast to talk about her new book, “The Right Kind of Wrong: The Science of Failing Well”— the 2023 Business Book of the Year.

Her research-backed guidance on failing well, what types of failures to avoid, and why high performing teams report more errors than lower performing teams will help your companies thrive. Teams thrive when people feel safe to speak up and take risks (even if they fail), and leaders play a crucial role in creating this culture.

On what happened when you were a PhD student at Harvard and you had a hypothesis about medical errors and teamwork:

My hypothesis was that better teams would have fewer error rates, which was a sensible hypothesis. It was a hypothesis that mirrored prior work that had been done in the aviation context.

To my great chagrin, the data seemed to be saying that better teams had higher, not lower error rates. I began to wonder that maybe the better teams aren't making more mistakes. Maybe they're more willing and able to report the mistakes they're making, or maybe they're just more able to speak up about it.

On how to encourage leaders to create an environment of psychological safety when they don't like taking risks:

If you don't like taking a risk, you are taking a risk. You're taking the risk of stagnation or the risk that your company or team will seize to be relevant over time. It won't catch up with you today or next week, but soon enough, it will.

The way I approach this is by first calling attention to the context that everybody's aware of already: your company or your team is operating in a volatile, uncertain, complex, ambiguous world.

They know that already, but they may not be calling attention to it enough to let other people know that they know that things could go wrong. In fact, things will go wrong.

First and foremost is to paint reality in a way that makes it explicit that you need people to speak up, that you know things will go wrong, and the more transparent and the quicker we are, the better off we are.

And two, distinguish between good failures and not-so-good failures. The good failures are the ones that bring us new information in new territory. They're the necessary failures that lead to innovation.

If you can be clear about the fact that we know and expect, and even value what I call intelligent failures, then you make it easier for people to speak up about them, but also easier for people to do their best to avoid preventable failures.

To err is human, we will all make mistakes. But when we're at our best, when we're vigilant and mindful, we can prevent most of them and catch and correct the rest.

On the three types of failures: intelligent, basic, and complex:

An intelligent failure is an undesired result in new territory where you couldn't have known in advance what would happen without experimenting. So they are in pursuit of a goal. You've taken the time to come up with a good hypothesis that you have good reason to believe it might work. And an intelligent failure is no bigger than necessary. You haven't made it larger than it needed to be.

Basic failures are single cause. Sometimes they're people not paying close enough attention. Sometimes they're overtired. Some of those basic failures are large, like when an employee accidentally checked the wrong box and wired the principal rather than the interest of a loan. That was a $900 million mistake at Citibank a couple of years back.

The third kind of failure is complex failures, and those are perfect storms. Those are failures caused not by one mistake or one factor, but by a handful of factors that come together in the wrong way or at the wrong time to lead to a failure. Any one of the factors on its own would not cause a failure. It's the unfortunate way they came together that leads to the failure.

There are many historically famous, but also every day accidents that qualify as complex failures.

On an example of a preventable failure where everyday fear, or lack of psychological safety, prevented someone from speaking up:

The Columbia shuttle tragedy of 2003 is complex failure. The shuttle reentered the earth's atmosphere and combusted, killing all of the astronauts, and of course, destroying the shuttle itself.

This was a complex failure that was a combination of some technical anomalies happening, some cultural factors coming together that made it not possible to end up catching and correcting in a timely way.

And there is an engineer at the very heart of this story who has doubts, has concerns, makes some tentative attempts to bring them up to his boss. He's kind of shut down, and then in a crucial mission management team meeting, he is present but feels unable to speak up when they start talking about this foam strike issue.

His explanation was he is just too low in the hierarchy to feel it was possible to speak up, and yet he's the one who had the most expertise. The accident investigation board concluded that it would not have been easy, but it was at least possible that a rescue attempt could have succeeded. This is a complex failure that was very much allowed by a strong sense of inability to speak up. That's the very reality of low psychological safety.

On the correlation between higher rates of agility and innovation, and trying new things, even if they fail:

If you only welcome trying new things when they work out, then they're not very new. They're kind of safe bets. And again, over the long term, that's not an innovative company. That's not a company that will likely thrive over the long term.

I think leadership is an educational activity, and this is an ongoing educational journey.

We need to continue to help people shift their mindsets from, "I got this" to "I wonder what would happen if," and shift their mindsets from the idea that we're supposed to have the answers and execute, hit our targets, and everything's supposed to be like a well-oiled machine to a mindset where it's, "Wow, we live in a volatile, uncertain world and we've got to be doing all sorts of things at all times to stay ahead of it."

It's just as important to do our part to minimize and prevent as many as preventable failures, but also to welcome the thoughtful experiments that end in failure.

Part of the answer is making those distinctions, because I think it's very hard for people to sign up for, “Let's fail all day!”

The only reason we're willing to sign up to try new things is when we are all on the same page about the kinds of experiments that might end in failure that are worth doing, and then the ones that we should try to avoid.

Get more insights

Get more strategies from our workplace culture experts at our For All™ Summit, April 8-10, 2025 in Las Vegas, NV.

Subscribe to Better wherever podcasts are available so you don't miss an episode.

Welcome to Better by Great Place To Work, the global authority on workplace culture. I'm your host, Roula Amire, content director at Great Place To Work. Amy Edmondson, Novartis professor of Leadership and Management at Harvard Business School joins me today. Renowned for her research on psychological safety, her new book, The Right Kind of Wrong: The Science of Failing Well is the 2023 Business Book of the Year. We talk about failing well, what types of failures to avoid, and why high performing teams report more errors than lower performing teams. For all the managers out there, how you respond when your people try new things, regardless of the outcome, makes all the difference in the world when it comes to agility and innovation. Amy left me with some food for thought in terms of taking risks in my personal life and how doing so might help us all have fewer regrets at the end of our lives. I hope you find this episode as inspirational as I did. Enjoy.

Hi, Amy. Thanks so much for joining me today. You are a Harvard Business School professor and author of the 2023 Business Book of the Year, The Right Kind of Wrong: The Science of Failing Well. Welcome to the podcast.

Amy Edmondson:

Thank you so much for having me.

Roula Amire:

Amy, you've spent a lot of your career studying failure, but before we dive in, let's quickly define failure so we're speaking the same language. Is it accurate to say failure is when things don't go like we thought they would or we wanted them to?

Amy Edmondson:

Yes, and in a negative direction, right? Because I think now and then, things don't go the way we expected, but in a unexpectedly happy direction. So a failure is an unintended and undesired result.

Roula Amire:

Got it. Okay, great. I'd love for you to start us off by sharing what happened when you were a PhD student at Harvard and you had a hypothesis about medical errors and teamwork. Can you share what your hypothesis was and what you learned?

Amy Edmondson:

So my hypothesis was that better teams, measured according to a validated survey instrument that measured teamwork and team leadership and various other things, would have fewer error rates, which was a sensible hypothesis. It was a hypothesis that mirrored prior work that had been done in the aviation context, and looking at cockpit crews as teams in simulators. And so that was my hypothesis. Again, it didn't seem like it was terribly controversial, maybe a little bit hard to measure and execute, but it was a reasonable hypothesis.

Roula Amire:

And what did you learn?

Amy Edmondson:

Well, to my great chagrin, when I got the data, my team survey data and trained medical investigators error rate data painstakingly collected over six months by essentially going door to door and asking people what you got. And everybody knew there was a big error study going on, so they were fully participating in it. When I got my data and ran my models, there was a significant correlation between the team measures and the error data. Unfortunately, it was in what I would call the wrong direction. So the data seemed to be saying that better teams had higher, not lower error rates. Now, that was a failure. There was an absolute failure to support the hypothesis I had put out there six months earlier. And make a long story as short as I can, what I began to wonder, in my initial depression and puzzlement, was that maybe the better teams aren't making more mistakes. Maybe they're more willing and able to report the mistakes they're making, or maybe they're just more able to speak up about it.

So when those nice nurses are coming to the unit to say what you got and looking at the reviews, maybe they're just more open than the other teams. And that suddenly started seeming like a pretty plausible interpretation of the data. Not at all solidly proven at that point, but just a possibility that I needed to investigate further.

Roula Amire:

Right. So it wasn't that those teams were committing more errors, they were just more honest in reporting them.

Amy Edmondson:

Right. And in order to understand how that could be, you have to realize that healthcare delivery in a hospital setting is a very complex activity. It's 24/7. It's lots of shifts in handovers. Each patient in a typical two or three day stay might be seen by as many as 50 or 60 different caregivers. So it's like it's inherently full of handoffs and complexity that partly motivated my hypothesis in the first place. It's like if you have really good teamwork, really good handoffs, you're going to have fewer error rates. But it also means it's easier to hide. A lot of things might go wrong but just not get spoken about. And of course, fortunately, most errors don't lead to irreparable harm. Some do, unfortunately, but most don't. So when we're collecting data on error rates, which is anything from a dose not quite right, wrong medication, wrong patient, a great deal of those errors don't cause harm. But if you don't have to speak up about, it's just a lot easier not to.

Roula Amire:

Which is what happens in many workplaces. But what you learned was that these high performing teams had more errors, not less.

Amy Edmondson:

More detected errors. That ends up being the subtle but important difference. Because at the end of that study, the real insight was we don't know the actual error rates. What we actually have measured are detected or reported error rates. And there was at least the possibility, which has since become more necessary probability, that not only were we not getting all the errors, but we were systematically getting higher error rates from better teams and lower error rates from less good teams, meaning fewer of the errors that were made were being revealed in the less good teams.

Roula Amire:

Right. And that's because they were on teams, high performing teams. They weren't punished for their failures, so then they could report them. And those results led you down the path of psychological safety, a term you're famous for coining. Let's stay on that point for a minute.

Amy Edmondson:

Yeah, sure. So what I was trying to intuit or describe is that there could really be differences, now, I think this seems very ordinary today, but differences in the work climate across groups in the same organization. And so it's not a corporate culture thing because everybody's in the same corporation or hospital, but that the work group level climate can really vary. And I just had this sense that might be true. And then I was able to send an ethnographer in who had no idea about the error data, no idea about the team data, so he was, in research terms, double blind to say, okay, what's it like to work in these different environments? And then he was able to come back and say, after a few days of observing, these places are really different. Some of them are really open, and some of them are really, his word, not mine, authoritarian environments.

And so then I thought I'm onto something, right? If you can have those kinds of differences in a workplace, seemed to me that that would matter a great deal for your ability to team up and learn and get better and catch incorrect errors so that harm doesn't happen, that you really need to create that kind of learning environment. And it was several years before I called it psychological safety, which I didn't coin the term psychological safety. That was in the clinical literature. I coined the term team psychological safety, because I think my insight and subsequent data we're able to show that this climate factor really does vary across groups. It lives at the team level. And so I called it team psychological safety, but I am often given credit for coining psychological safety. I think that was probably Carl Rogers or somebody like that.

Roula Amire:

You're saying it's not a culture thing, it's a team thing.

Amy Edmondson:

Yeah, it's influenced. Fortunately, I had one study of six corporations, 26 teams, so a handful of teams per company. And there, I was able to show, rather systematically, that, yes, companies do differ in psychological safety, but within companies, teams differ usually even more because it's very much a leadership in the middle kind of phenomenon. It's your proximal leader, your team leader, your branch manager, your nurse manager. It's this sort of authority figure who is closest to where the work that I do lives who has the biggest influence on the interpersonal climate.

Roula Amire:

Right. So let's talk about leaders then. For a minute. They have to model the behavior they want to see in their employees. But failure isn't something executives like to talk about, even though you've proven there's power in talking about failures. Even in my world of storytelling, a leader does not want to share what went wrong. But what makes stories powerful are lessons learned, mistakes, challenges. A story of perfection isn't that interesting/ it can be kind of bland.

Amy Edmondson:

It's true. If there's no hero's challenge, it's not a very good story.

Roula Amire:

Exactly. So how can we encourage leaders to create an environment of psychological safety when they don't like taking a risk themselves?

Amy Edmondson:

If you don't like taking a risk, you are taking a risk, right? You're taking the risk of stagnation or the risk that your company or team will seize to be relevant over time. It won't catch up with you today or next week, but soon enough, it will, right? So we're all in need of some risk taking. I do think we can take smarter risks rather than less smart risks. But the way I approach this is by first backing up and calling direct attention to the context that everybody's very aware of already. I'm not bringing any new information when I say your company or your team is operating in a volatile, uncertain, complex, ambiguous world. They know that already, but they may not be calling attention to it enough to let other people know that they know that things could go wrong. In fact, things will go wrong.

First and foremost is like paint reality in a way that makes it explicit that you need people to speak up, that things will go wrong. And just the more transparent and the quicker we are, the better off we are. So that's one. And then number two is distinguish between good failures and not so good failures. And the good failures are the ones that are bringing us new information in new territory. They're the necessary failures that lead to innovation. They're the necessary failures. Anytime we want to move into a new market or into a new product line. It's new, so we don't have it all ironed out.

So there will be successes and failures along the way. And so if you can be clear about the fact that we know and expect, and even value the what I'll call intelligent failures, then you make it easier for people to speak up about those, for sure, but also easier for people to sort of manage the difference, and to know, to sit up straight and do their very best to avoid preventable failures, to minimize mistakes, to error... As human, we will all make mistakes. But when we're at our best, when we're vigilant and mindful, we can prevent most of them and catch and correct the rest.

Roula Amire:

We learn in your book that not all failures are created equal. You outline three types, basic, complex, and intelligent, which you just mentioned. And you say intelligent failure is the type of failure that we should love. So I'd love for you to give just a brief definition of each in the context of the workplace and why intelligent failure is the right type of wrong.

Amy Edmondson:

Absolutely. So even as a scientist or researcher, I still am much preferring to be right than wrong. So I'll be honest about that. If I have a hypothesis and I go collect the data and my hypothesis is supported, I love that, right? And I wouldn't be a very good scientist if I wasn't willing to also know that some of my hypotheses won't be supported, and almost to try my best to welcome that data as heartily as I welcome the other data because it's necessary. So the three kinds of failure, and I'm talking here... I'll talk first about intelligent failure. An intelligent failure is an undesired result in new territory. We truly couldn't have known in advance what would happen without experimenting, without trying something. So they are in pursuit of a goal. The territory is new, we don't yet have the knowledge we needed for it. Number three, we've done our homework. We've taken the time to sort of come up with a good hypothesis that we have good reason to believe it might work. And then fourth, an intelligent failure is no bigger than necessary.

So it is the size experiment that will help us get new information in new territory, but it's not wasteful. We haven't made it larger than it needed to be. And so those are the criteria that allow me to say, yes, I'm disappointed, and we needed this in order to get the next step forward toward our goal, whereas basic failures are single cause. Many failures, I talk about many stories in the book are failures that are caused by a single human error. Sometimes they're people not paying close enough attention. Sometimes they're overtired, whatever. Make a mistake, it leads to a failure. Some of those basic failures are large, like when an employee accidentally checked the wrong box and wired the principal rather than the interest of a loan. That was a $900 million mistake at Citibank a couple of years back, and they were not able, actually, to get those funds back, right? So unbelievable in terms of magnitude of a basic failure, but it's a basic failure, single error.

Now, if we were to really step back, we'd say you should not have a process whereby it's that easy to make an error that could cause that large a failure, right? But that gets to system design. And the third kind of failure, I call complex failures. And those are the perfect storms. Those are failures caused not by one mistake or one factor, but by a handful of factors that come together in just the wrong way or at the wrong time to lead to a failure. Any one of the factors on its own would not cause a failure. It's the unfortunate way they came together that leads to the failure. And there are many historically famous, but also every day accidents that qualify as complex failures.

Roula Amire:

In your book, you cite Toyota as an example of a company finding and fixing failure well. Can you share that with our listeners?

Amy Edmondson:

Yes. So Toyota is a wonderful example of a company that takes human fallibility and operational complexity very seriously indeed. And it has created a culture and a set of tools and systems that encourage, and even reward people speaking up quickly about not only failures, but more importantly, potential failures. When they're just not a hundred percent sure that something is perfect, they are encouraged to do what's called pull the end on cord and say, this doesn't feel quite right. And most of those requests are not actual problems, right? Most of them are just these minute learning opportunities where we take a look at it, and then realize all is well. And only a minority of the polls end up being real problems, but they realize it is so much better to run an operation where people are airing on the side of caution. And it doesn't take long, right? It takes no time at all, no real resources at all, but prevents the very undesirable failure of a customer getting a faulty car.

What I love about the Toyota production system is it is a system. It is not one thing. It's a set of elements. It's the culture, it's the tools, it's the training that all sort of come together to create a profound learning operation.

Roula Amire:

And in cultures where you can't share failures, that doesn't mean they don't happen, they just stop hearing about it. Even our research on innovation, everyday fear was one of the top barriers preventing employees from offering new ideas. Many of the failures you've studied were preventable had someone felt comfortable to speak up. Can you share an example?

Amy Edmondson:

Absolutely. But may I first say I love the term everyday fear because it captures a lack of psychological safety quite precisely, right? It is not panic or complete paralysis. It's just that sort of everyday fear that leads people to err on the side of holding back when what we really need is to err on the side of speaking up and leaning in. So actually I've just come from my classroom at Harvard Business School today where I taught a case study on the Columbia shuttle tragedy of 2003, which is an extraordinarily good example of the question you asked, which it's a complex failure, is the shuttle reentered the earth's atmosphere and completely combusted, killing all of the astronauts, and of course, destroying the shuttle itself. And this was a complex failure that is a combination of some technical anomalies happening, some cultural factors coming together that made it not possible to end up catching and correcting in a timely way.

And there is an engineer at the very heart of this story who has doubts, has concerns, makes some tentative attempts to bring them up to his boss. He's kind of shut down. And then in a crucial mission management team meeting, he is present but feels unable, just absolutely disabled, unable to speak up when they start talking about this foam strike issue. And his explanation was he is just too low in the hierarchy to feel it was possible to speak up, and yet he's the one who had the most expertise. The accident investigation board concluded that it would not have been easy, but it was at least possible that a rescue attempt could have succeeded, that had they known enough to look into to get imagery from satellites in space to just check whether or not there was a hole in the leading edge of the wing, they could have done something about it. So this is a complex failure that was very much allowed by a strong sense of inability to speak up.

Roula Amire:

Would you describe that team... Is it accurate to conclude he didn't feel that he had psychological safety, meaning he didn't feel he could speak up and say something, so without that, you kind of just keep your mouth shut so you don't get in trouble?

Amy Edmondson:

Yes, he would not have used the term psychological safety. But when asked back then, "Why didn't you speak up? by ABC News anchor, for instance, he said, "I just couldn't do it." And he put his two hands up, six inches apart from each other and he said, "I'm too low down here, and she," meaning the mission management team leader "is way up here." And that is as good a description of a lack of psychological safety as I've ever heard. It's not terror or fear. It's more like, I just can't. How could I in a hierarchy when I'm not asked for my opinion. It's just not-

Roula Amire:

It's not an option.

Amy Edmondson:

... an option. It doesn't feel like an option. That's the very reality of low psychological safety.

Roula Amire:

Hey, better listeners. Want to put your headphones down and meet culture leaders in person, network and learn from the most innovative companies across every industry, hear from bestselling authors like Angela Duckworth and the Emmy nominated actress, Mindy Kaling? Then mark your calendars May 7th through 9th and join us in New Orleans at the Great Place To Work For All Summit, the can't miss company culture and leadership event of the year. Use the code better2024 to save $200 off. Registration before April 7th. Find the code and link in our episode bio. See you there.

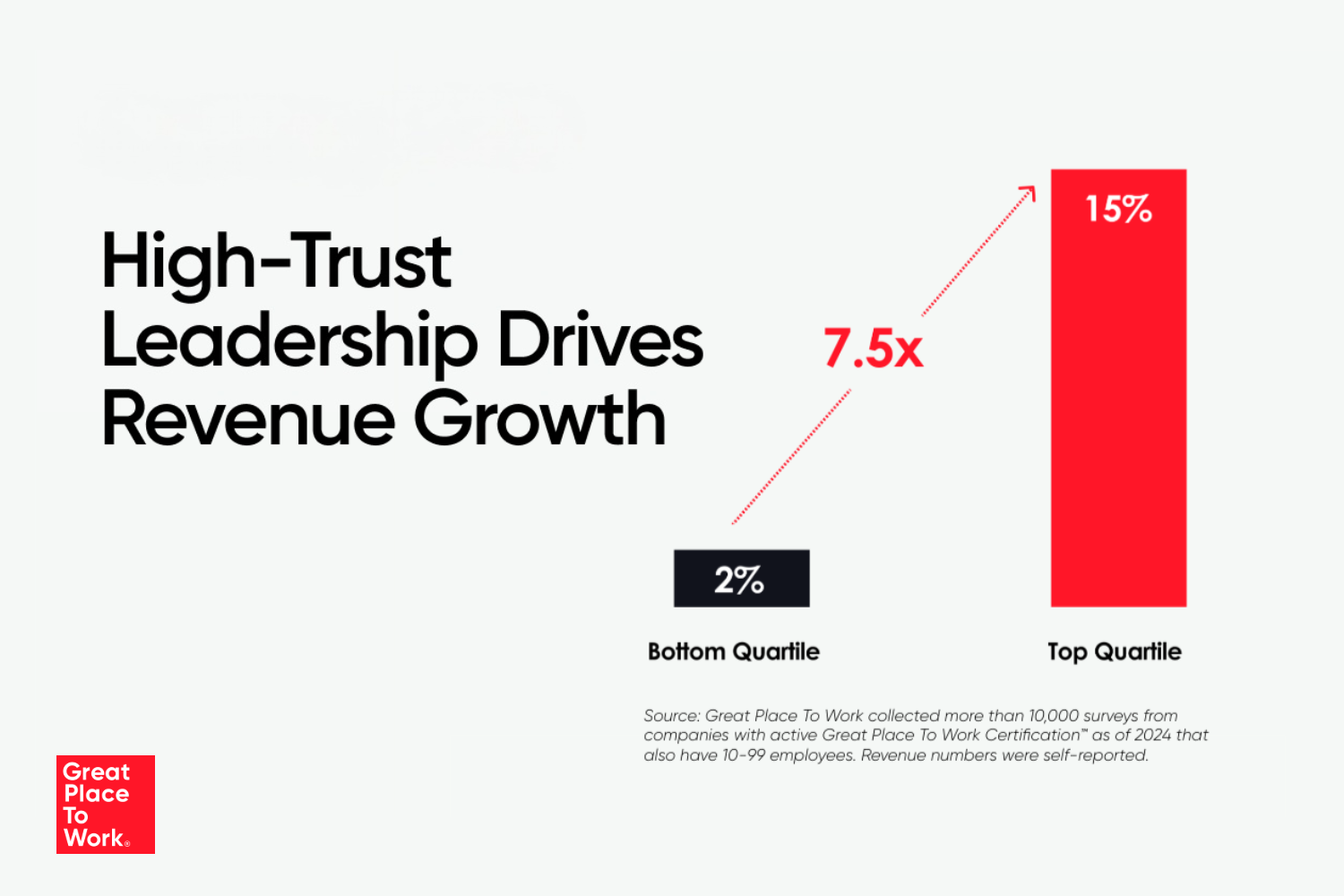

I'd like to get your thoughts on the correlation we found between failure and agility. Our research at Great Place To Work found that when employees say their company celebrates trying new things, even if they fail, those employees are 3.1 times or 210% more likely to say their organization quickly adapts to change. So celebrating trying new things is by far the top driver of agility, and that's according to 1.3 million employees. We also found that employees are twice as likely to report having a lot of innovation opportunities when they report working in an agile workplace. I wanted to get your take on this ripple effect of higher rates of agility, higher rates of innovation, something every leader wants in their people, especially in the age of AI. If companies shift how they see failure, because when it's celebrated, again, to your point, the right type of failure, agility rates are higher and innovation is higher. So how can we help, this is what your entire book is about, but help companies shift their mindset and learn from failures when the return is so high on the business results they want?

Amy Edmondson:

I love those data. I love those results. Would love to study them more, but they make perfect sense to me. And all of these factors travel together, the sense that my company is agile, the sense that my company welcomes trying new things, even when they don't work out. If you only welcome trying new things when they work out, then they're not very new. They're kind of safe bets, as it were. And again, over the long term, that's not an innovative company. That's not a company that will likely thrive over the long term. So all of this, it's a kind of ongoing... I think leadership is an educational activity, and this is an ongoing educational journey.

We need to continue to help people shift their thinking, shift their mindsets from, "I got this" to "I wonder what would happen if," and shift their mindsets from the idea that we're supposed to have the answer and execute and hit our targets and everything's supposed to be like a well-oiled machine to a mindset where it's wow, we live in a volatile, uncertain world and we've got to be doing all sorts of things at all times to stay ahead of it. And it's just as important to do our part to minimize and prevent as many as possible preventable failures, but also to welcome the thoughtful experiments that end in failure. So I think part of the answer is making those distinctions, because I think it's very hard for people to sign up for, okay, sure, let's fail all day. The only reason we're willing to sort of sign up to try new things is when we are all on the same page about the kinds of experiments that might end in failure that are worth doing, and then the ones that we should, thank you, try to avoid.

We already know here's the recipe. It works perfectly every time. We don't say, "Oh yeah, go ahead and deviate from that recipe."

Roula Amire:

The same is true outside of the workplace. People don't like to deviate or like to change, which something I wanted to ask you about. We focus most of our discussion today on the workplace for obvious reasons, but your book is filled with other examples outside of work and in life. I don't know if you'll think this is a stretch, but this is where my mind went. There's a book I read a few years back that has stuck with me called The Five Regrets of the Dying. Okay, it's written by a hospice nurse. I highly recommend it. And the number one regret is not living a life true to yourself, but living the life others expected of you. And I feel like that falls into taking what you perceive as a risk and going for it.

Oh, shoulda, woulda, coulda. Those people at that regret, maybe they didn't want to fail or disappoint others if it didn't work out. But as we've learned today, playing it safe doesn't pay off. You might end up with this big life regret. So if we want to help people avoid that regret, does your research prove the adage, no risk, no reward? Am I simplifying things too much?

Amy Edmondson:

I wouldn't claim that my research proves that, but I think there's plenty of other evidence that does prove it. And in the last chapter of the book, which I call Thriving As A Fallible Human Being, I do try to pull together a handful of those things. And in fact, I do look at research on regrets because it turns out, much like the book you described, that we are more likely to regret not taking risks than having taken a risk and failed at something. Those are not the ones that... It's like, at least I tried. I went out for the basketball team, I got rejected, but at least I tried. No harm done really. Maybe a little embarrassment. Whereas the risks that people take, Dan Pink has written about this, that are really memorable, the person I didn't ask out, even though I really wanted to, the company I didn't start, the promotion I didn't try to get, the move, the sort of adventurous move I didn't make that might've expanded my horizon.

So one of the things I say is, and this is really playful, but I say fail more often, right? To have a full and fewer regret failed life, fail more often. Of course, I don't really mean wake up this morning and look for places to do damage. What I mean is take risks, right? Take the kinds of risks that might take you somewhere really exciting or might not, but be willing to have the discomfort of failing.

Roula Amire:

Can you share one of your own with the listeners?

Amy Edmondson:

Oh gosh. Well, it's funny because in the book, I write about my friend Laura in her 40s joining a ice hockey team. She had no ice hockey experience. That was a good one. You're going to fall a lot and all that. But when I was... My first job out of college, I was an engineer. I was doing mostly calculations on geodesic domes. I was working for Buckminster Fuller. And one day, he asked me whether I could do some engineering drawings, some technical drawings for him. Now, I actually hadn't taken any engineering drawing classes, and I really didn't have the skill. I was a pretty good... I could sit and draw. I had taken drawing classes in art, right? I was a pretty good, pretty draftsman in that sense, but I didn't have the technical skills, but I said yes. And it was, I absolutely could have, and then at that moment, expected that I would fail. But I went to the public library and got a big fat book called Engineering Drawing and sat down to figure out, well, how are they labeled? What do you do?

And then I did the work, and then I brought it to him, and he basically said, "Very good. Now, would you do some more?" Right? And I thought... I had that moment of panic when I said, why am I saying yes to this? Right? I wanted to expand. It was pretty early on. I'd been there only a month, and I'd been doing a lot of very routine work, and I really wanted a chance to do more. It felt a little bit like it was a lie, but it was a risk. It was a jump in and risk, and it worked out, of course, great. But I can tell you some where... The story we started out with, that was a... I said yes to this medical error study. I thought it would be pretty straightforward. I'd show better teams make fewer mistakes, and everybody would be happy. I failed. The journey toward a more interesting research thread took a while, followed on the heels of that failure, but not automatically. I had to, I guess implicitly. I'm not sure... I certainly wasn't thoughtful about it at the time.

But by saying yes to the medical error study, I had to be willing to end up being wrong or to fail, and also willing to let it take me somewhere else that was even potentially more interesting.

Roula Amire:

Right. Thankfully. We're all thankful for that.

Amy Edmondson:

Thank you.

Roula Amire:

I ask all my guests for advice. They go back and give their younger self. Do you have something to share?

Amy Edmondson:

I'd like to say take more risks, although I took a lot of risks.

Roula Amire:

You did. You have.

Amy Edmondson:

It worked out, right? I mean ultimately, in the grand scheme, not one by one. But the advice I would absolutely like is just do what you did, but don't feel so anxious about it all the time. I caused myself so much more suffering than I needed to because of that sort of conviction, the anxiety that it wasn't going to work out. There were just a thousand times where I just thought, okay, this is the end. I'm going to have to drop out of graduate school. Okay, this is the end. I'm going to get fired on the spot for drawing that drawing.

Roula Amire:

Catastrophizing.

Amy Edmondson:

The catastrophizing was busy at all times and utterly unhelpful. I can't think of a single time when the catastrophizing actually helped me achieve a goal

Roula Amire:

Or was true, right?

Amy Edmondson:

Or was true. Right. Right.

Roula Amire:

What you worried about, I'm sure never actually happened.

Amy Edmondson:

It was all of that unnecessary pain, moderate pain that didn't help me and didn't really support the thinking I'm trying to imbue in this book, which is, yes, take those risks, and no, don't beat yourself up along the way or when they don't work out, or when they do work out.

Roula Amire:

Is there anything you're reading that you'd like to recommend to our audience?

Amy Edmondson:

Well, I am eight years late, but I'm halfway through The Road To Character by David Brooks. And I have to say it's deeply moving. The tagline is resume virtues versus eulogy virtues. It's really a very thoughtful look at character, and what does it mean? I think to be present as a human being in service of others, not in a selfless sense, but in a fully engaged sense versus... And I think over the years of my adult life, the shift from who are you and what are you contributing toward, how important are you, has been going in the wrong direction. I think too many people, young and old, are... They want to be successful, famous, look good in the eyes of others, rather than actually feel that deeper sense of fulfillment from making a contribution that you uniquely are there to make.

Roula Amire:

That sounds like a great recommendation. Thank you, Amy, for joining us today. I enjoyed the conversation. I learned a ton, and I hope to continue to fail well.

Amy Edmondson:

Thank you. Failing well is as much about taking risks and having experiments that don't all turn out as about being thoughtful and cautious and preventing the basic and complex failures that you can.

Roula Amire:

Thanks for listening. If you enjoy today's podcast, please leave a five star rating, write a review, and subscribe so you don't miss an episode. You can stream this in previous episodes wherever podcasts are available.