High-trust workplaces can create a different career path that helps source crucial talent.

Ageism is a pernicious and ubiquitous force in the workplace.

Among job seekers who are 50 or older, 59% believe that their age created obstacles during the hiring process. Some studies suggest that as many as 93% of older adults have experienced ageism, and 42% of hiring managers admit they consider age when reviewing résumés.

Even so, ageism often goes unreported. Only 40% of those who experienced ageism filed a charge or complaint with someone at work or to a government agency, per a Hiscox survey.

The experience is made more relevant by a slowing economy.

“What is so challenging right now is that this is a brutal job market,” says Colleen Paulson, founder of Ageless Careers, a firm that advises older job seekers. “You lose that good job, and it’s taking over a year to find something else.”

Complicating the picture is the rise of AI, which might filter out résumés from older applicants or contribute to perceptions of an inability to adapt to new business realities.

“We pivoted from the fax machine,” Paulson says of older workers and their experience being agile. “I’m a Gen Xer. I’ve lived through all the change. We can do this too.”

High-trust leaders can choose a different path

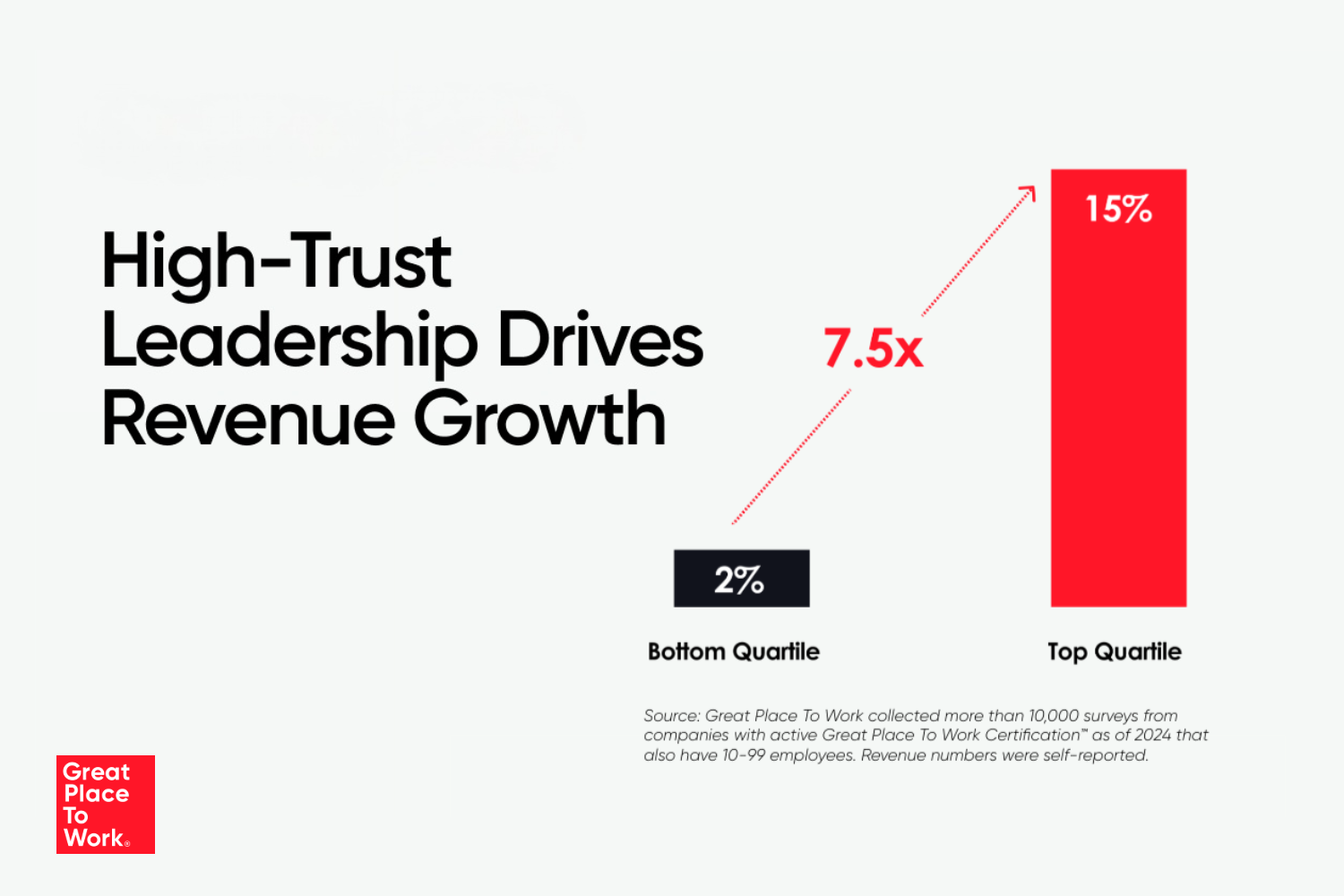

For companies that want to change this dynamic, the first prerequisite is trust.

Older workers must trust their employer enough to have meaningful conversations about their career, discuss new options, or explore different choices.

“If you’re my manager and I know I can trust you, then I’m okay to tell you that I might want to retire in three years because you’re not going to hold that against me,” Paulson gives as an example.

One company doing things differently is Schneider Electric, a global energy technology company and a Great Place To Work Certified™ organization. For the last several years, the company has deployed its Senior Talent Program to offer equal opportunities, including growth and development initiatives, to experienced employees based on their career aspirations and interests.

“We realized that there was a potential to enhance and further engage this part of the population,” says Michael Fossat, vice president of human resources and an early leader of the senior talent program.

The program recognizes that senior talent have priorities and interests and commits to support each person to create their desirable future, no matter if they:

- Want to stay in their current role or level within the organization

- Want to accelerate their career

- Want to explore opportunities to mentor or teach

- Are preparing for their retirement

Schneider offers tailored support for each group, such as leadership training for those wanting to accelerate their careers or external placements at NGOs for those who want to share their expertise through teaching or mentoring. For those wanting to continue their current roles, the company provides a large portfolio of learning courses.

For those choosing retirement, the program has a variety of options: part-time work prior to retirement, compressed or four-day workweeks, and opportunities to return to the company for short stints post-retirement.

In Japan, Schneider is recruiting one-third of recent retirees to come back three days a week.

To adapt for cultural differences and sensitivities from one geography to another, the company offers flexibility to each country to adapt the global vision to their local reality. “Obviously, it’s not the same having a woman leaving at 55 in China and another employee still working at 80 in the U.S,” Fossat says.

The importance of listening

What unlocks a program like the global offering from Schneider Electric? Listening to the needs of senior talent — a widely overlooked demographic in many organizations.

That’s why Schneider Electric carefully measures whether employees are having a career conversation with their manager and how it changes their motivation in annual employee surveys. In the past year, the engagement of employees in the “senior” demographic has increased six points globally — a sign the program is succeeding.

Schneider also held workshops and focus groups to learn more about the challenges and aspirations for experienced employees. “My advice is, listen to them and you will probably see what is missing,” Fossat says.

Two topics that surprised the team in conversations with older workers: the impact of health issues on retirement decisions and a level of sensitiveness around the term “senior talent”. What began as a delicate subject has evolved into a positive dialogue about experience, legacy, and shared success.

Changing hiring practices

For Paulson, companies should think about how to combat assumptions around age in the hiring process.

“In talking with folks who are experienced, the biggest pain point is, let me get in front of you and give me 15 minutes to tell you my story,” she says. Whether recruiter bias or faulty technology is to blame, older workers are often overlooked, causing companies to miss out on valuable talent.

“I had a client recently who is 67 who landed at a startup, and he had never worked for a startup, but he had worked for some big-name companies,” Paulson says. “Because he has 45 years of work experience, he could step in and do a lot of different things.”

For companies looking to hire, it’s vital to challenge assumptions about a role. “You might be getting two or three different people in this one package because they’ve held so many different roles,” Paulson says. “And it really is something that a lot of companies overlook.”