Belonging, Camaraderie, Caring

Here’s how leaders should make space for authenticity and humanity within the boundaries of professionalism.

In the early days of the pandemic, when pets and children started to appear in the background on Zoom calls, we celebrated the vanishing boundaries between work and life outside the office.

We assumed that this new lens on shared humanity would provide context to build a stronger esprit de corps in the workplace.

But as the pandemic era stretched into months and years, there was a backlash.

Leaders began to ask: “Does the whole self actually belong in the workplace?”

Tech investor Marc Andreesen made his case in a comment on X: “The one thing you should never, ever, ever do is bring your full self. Leave your full self at home where it belongs and act like a professional and a grown-up at work and in public.”

Others pointed out that the debate over bringing a complex human experience to the workplace was overfocused on the experience of white-collar office workers.

“Nobody is asking a line worker or customer service representative to add more personal vulnerability to the enterprise,” wrote columnist Pamela Paul in The New York Times. “For most gainfully employed people, it’s not work’s job to provide self-fulfillment or self-actualization. It’s to put food on the table.”

Some are questioning how leaders show up in the workplace. A recent article in the Harvard Business Review argues that unfiltered sharing from leadership doesn’t help employees build trust and confidence.

“Authenticity is often conflated with honesty,” writes Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic. “But in leadership, what matters more is emotional intelligence: the ability to manage your own emotions and influence the emotions of others.”

Making room for more than a professional mask

The best workplaces make space for more than the narrow definition of professional accomplishment.

Great Place To Work research shows that when employees feel like they can “be their true self” at work, they are two times as likely to look forward to going to work and 50% more likely to want to stay in their job.

When employees feel like their manager cares about them as a person, including their responsibilities and goals outside the workplace, they are 40% more likely to report being able to innovate.

That doesn’t mean that employees don’t filter their personalities in work situations.

“Most people would say they don’t bring their ‘whole’ selves to work,” says Julian Lute, strategic advisor at Great Place To Work. “They try to bring the acceptable parts of their whole selves that keep them employed at any time and with any leaders.”

“There’s a sanitized part of our whole self that the organization actually wants, because the reality is work has to get done,” says Sarah Wittman, assistant professor of management at George Mason University’s Costello College of Business.

Instead, Wittman recommends thinking about the workplace as an exchange of resources.

“What community and resources can we provide to people?” she recommends asking. “What sort of resources do you want the organization to be for you?”

Meaningful work and purpose

Where should business leaders draw the boundary? One helpful idea is to consider the role of purpose.

“Employees want to have the feeling or experience that they aren’t leaving critical parts of who they are behind for the sake of a paycheck,” Lute says. And one way to consider what might be a “critical part” of the employee is to ask about purpose.

“Purpose plays a vital role,” Lute explains. “Do your values align with the work you do? Do you feel connected to the customers you serve? How does your employer help you fulfill other important roles in your life, like father, husband, member of your community?”

To ensure there is alignment, leaders have to spend time listening and getting to know their people.

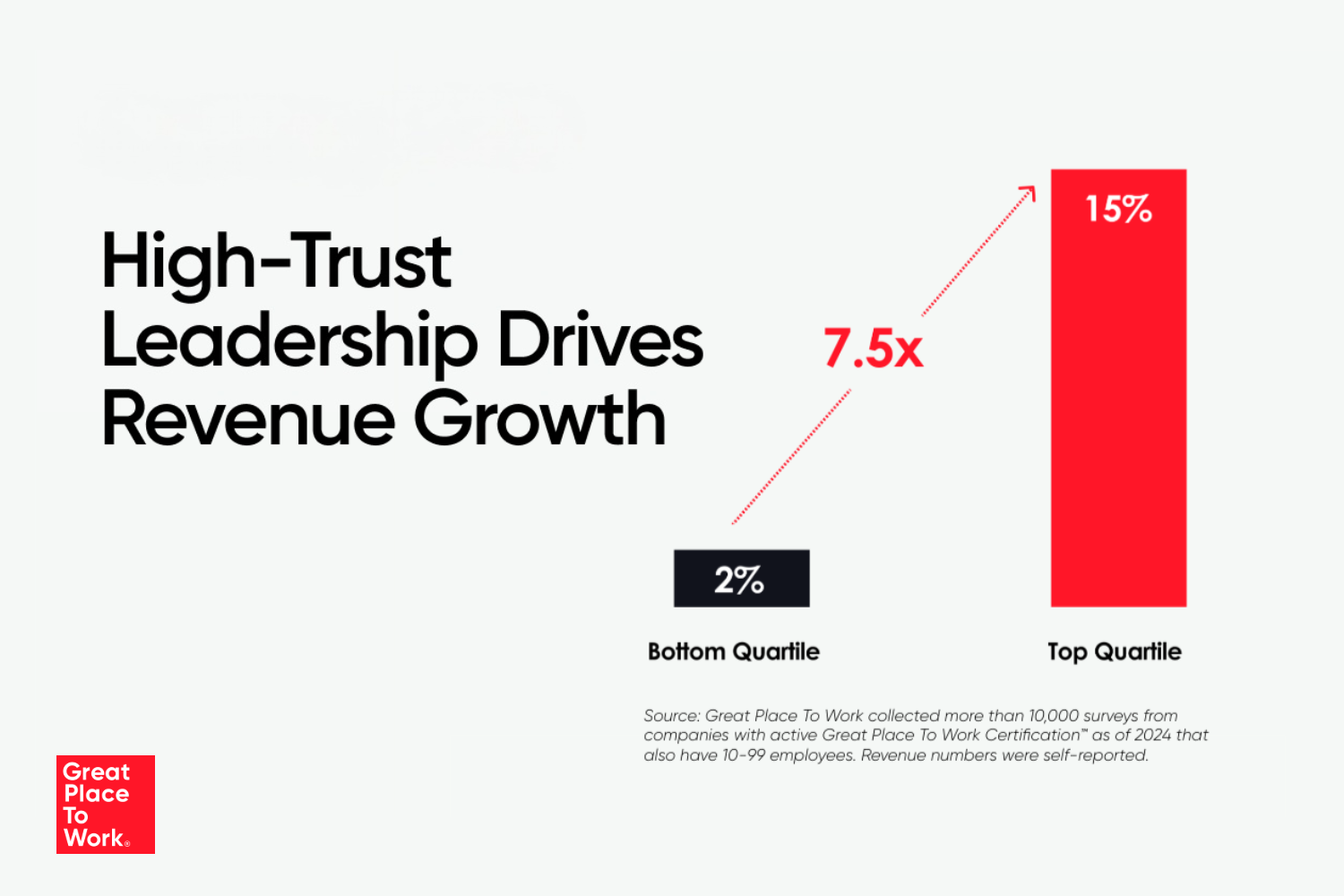

“Your leader has to know and care about you inside and outside of work because the parts affect the whole,” Lute says. That’s why listening is the most important of the nine high-trust leadership behaviors: Knowledge enables empathy and caring.

How to uncover untapped resources

One way for leaders to learn about hidden facets in their workforce is with Wittman’s exercises around uncovering “resources.”

“You might be a friend to some teammates, or mentor others in the organization,” Wittman explains. These are “resources” that you represent in the workplace, but you might represent other resources as well.

“There are hidden diversities, things that no one is going to know about you,” Wittman says. Maybe you play a musical instrument or have a really great sense of direction, skills that don’t immediately translate into a workplace context, but can unlock a healthier relationship between co-workers.

Wittman runs an exercise where participants write down “resources” that they have on sticky notes and place them on a whiteboard. The group, anywhere from five to 30 people, then makes connections between those resources and potential needs across the group.

“Even seeing things that you don’t need sparks a different way of seeing other people,” Wittman says.

That knowledge sharing can make all the difference, according to research on the drivers of innovation and team performance.

“Getting to know people is irreplaceable,” shared author and leadership expert Vanessa Druskat in an interview with Great Place To Work. “Once you get to know one another, you can start giving one another feedback. The No. 1 norm in my model — it’s linked to performance in every team I’ve ever studied — is getting to know one another.”